“Seasons Greetings, from Ferguson,” November 29, 2014. Mike Tigas, via Flickr

Richard Rothstein of the Economic Policy Institute says we need to remember the big picture of race relations in Baltimore:

The police behavior is something that should be remedied. It’s a terrible criminal operation on the part of the police departments. But it doesn’t start with police departments. When you have a low-income population concentrated in the area, little hope, unemployment rates in places like inner city of Baltimore … two and three times the rate for whites, well, you get behavior in those kind of communities that reinforces police hostility. It becomes a cycle of misbehavior and police aggression, and it’s attributable to the concentration of disadvantaged families in very crowded inner-city communities.

When an unarmed black man dies after a confrontation with police, there is a natural tendency to focus on racist police officers or racist police departments. We saw this after the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, and we saw it, too, after the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson and Walter Scott in North Charleston. Without a doubt, there are plenty of bigoted bad apples to be found, as seen in the shockingly racist emails unearthed in the Department of Justice investigation into Ferguson’s police department. But we also need to consider that big picture, or what sociologists call social structure: institutions like the economy and political system and the roles that people take up within them. After all, the modern-day factors pushing down poor African American communities—and pulling them into hostile encounters with police—involve more than just racial discrimination (or at least discrimination of the plain-vanilla variety).

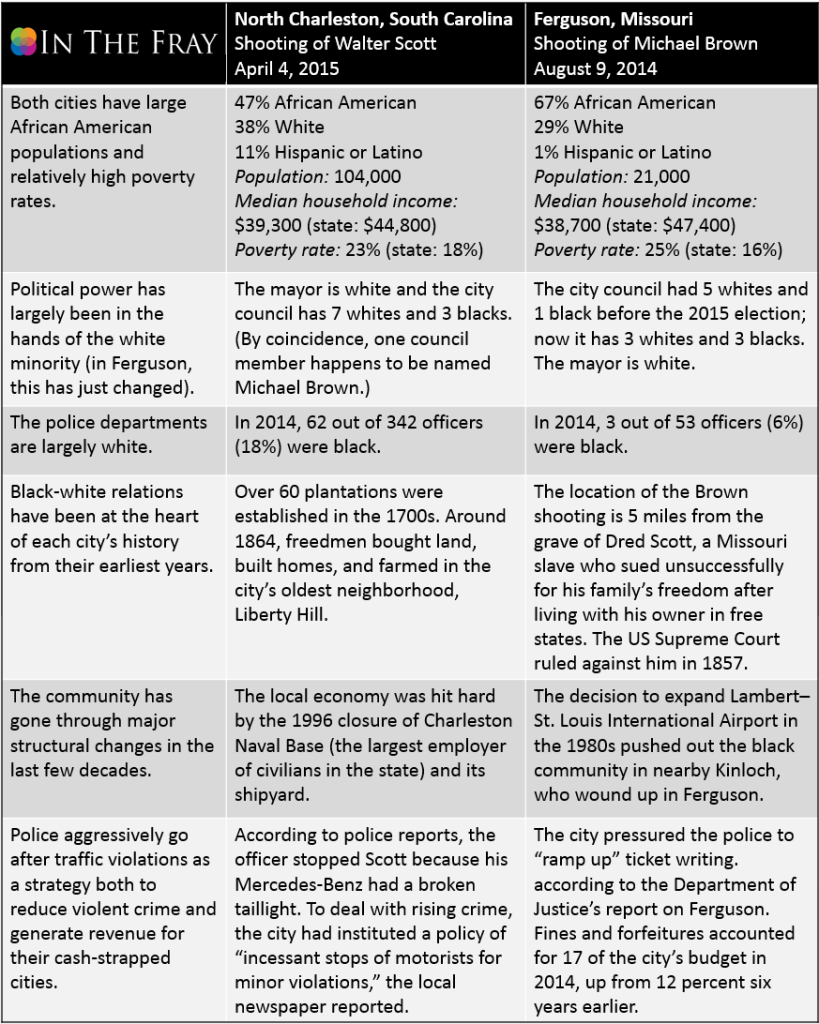

Here is a handy chart that illustrates what I mean, using the examples of Ferguson and North Charleston—two cities with a few striking similarities.

As Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson points out, systematic racial discrimination was what originally put African Americans in their place—stuck in segregated neighborhoods and blocked from educational and job opportunities (disclosure: Wilson was my advisor in graduate school). That past has lingered on today. In the latter half of the last century, the sorts of racially motivated housing policies that Rothstein discusses worsened the plight of the people left behind in cities like Baltimore.

On the other hand, Ferguson gives us an example of policies that were not explicitly racial, but that nonetheless helped trap many African Americans in poor, crime-ridden, aggressively policed neighborhoods. Beginning in the 1950s, decisions to situate new highway extensions and other infrastructure projects within low-income neighborhoods resulted in the razing of once-vibrant communities. Again, African Americans were hit the hardest. In the St. Louis metro area, the expansion of Lambert–St. Louis International Airport in the eighties all but destroyed the black community of Kinloch, located near Ferguson. “Many of the residents displaced by this wasteful construction project,” Jeff Smith writes, “have ended up in Ferguson—specifically, in Canfield Green, the apartment complex on whose grounds Michael Brown tragically died.”

More generally, policies about where to build airports and route highways may have racial motivations behind them. (“We might ask,” Wilson writes, “whether such freeways would have also been constructed through wealthier white neighborhoods.”) But larger structural changes that have had little or nothing to do with race have also harmed African Americans disproportionately. Beginning in the eighties, cities across the country were devastated by downsizing. Corporations shipped jobs overseas in droves, and the federal government sharply cut direct aid to cities and trimmed industries that once sustained many cities—in North Charleston’s case, closing Charleston Naval Base, once the largest employer in the state. As Wilson notes, African Americans have not been the only ones affected by these seismic economic shifts. But they have been particularly vulnerable because of their low levels of skill and education relative to whites, a gap that has made it more difficult to find good jobs to replace the ones their communities lost. Few jobs and high poverty, in turn, lead to more crime, which leads to more potentially violent confrontations with police.

Beyond their need to clamp down on crime, however, the police have other, more unseemly incentives nowadays to get in the faces of the citizens they are sworn to protect. A lackluster local economy has pushed many cities to become creative about generating revenue. In Ferguson, the city’s various streams of cash have dwindled in recent years—except for fines and forfeitures. Traffic tickets and the like, it turns out, have made up for Ferguson’s budget shortfalls in recent years. As the Department of Justice report made clear, however, the push by city officials to “ramp up” ticket writing has worsened racial tensions: “Many officers appear to see some residents, especially those who live in Ferguson’s predominantly African American neighborhoods, less as constituents to be protected than as potential offenders and sources of revenue.”

The kinds of structural changes that have hammered cities like North Charleston and Ferguson and Baltimore—and cities across the country, for that matter—have made the situation on the streets all the more toxic and volatile. Body cameras and DOJ investigations are a good first start, but the problem, as usual, goes much deeper.

Sources for the chart

North Charleston: Census data, City of North Charleston (naval base, city council, history), Post and Courier (demographics, traffic stops), New York Times.

Ferguson: Census data, New Republic, Associated Press, USA Today, NPR, US Department of Justice, City of Ferguson.

The post The Big Picture of Baltimore, Ferguson, and North Charleston appeared first on In The Fray.